This is a topophonic telestereoscope, a machine I built for exaggerated three-dimensional vision and sound. It is a mash-up of two nineteenth-century inventions: the topophone and the telestereoscope.

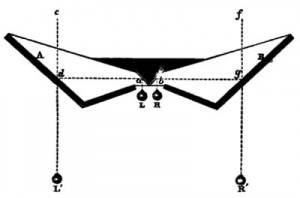

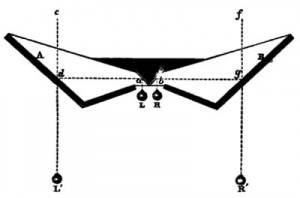

The topophone, shown at right, was invented by Alfred Mayer, a professor of physics at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ, to help locate distant sounds. It worked by artificially exaggerating the distance between the ears, and amplifying their inputs. An 1880 Scientific American article, from which this image is drawn, explains the topophone’s intended purpose:

The topophone, shown at right, was invented by Alfred Mayer, a professor of physics at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, NJ, to help locate distant sounds. It worked by artificially exaggerating the distance between the ears, and amplifying their inputs. An 1880 Scientific American article, from which this image is drawn, explains the topophone’s intended purpose:

The aim of the topophone, which was invented and patented by Professor A. M. Mayer, last winter, is to enable the user to determine quickly and surely the exact direction and position of any source of sound. Our figure shows a portable style of the instrument; for use on ship-board it would probably form one of the fixtures of the pilot-house or the “bridge,” or both. In most cases arising in sailing through fogs, it would be enough for the captain or pilot to be sure of the exact direction of a fog horn, whistling buoy, or steam whistle; and for this a single aural observation suffices.

Acoustic locators were later widely used to pick up the distant rumble of aircraft engines–until the invention of radar during World War II rendered them all but obsolete. Below is a photograph of Emperor Hirohito touring Japanese “war tubas.”

And here’s an American version of the same technology, being demonstrated in 1921:

The telestereoscope was first described in 1857 by the German physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, who is best remembered for his treatise on the conservation of energy, and for inventing the opthalmoscope. The device uses widely separated mirrors to artificially increase intra-ocular distance and exaggerate the user’s perception of depth, giving “a much clearer representation of the form of a landscape than the view of the landscape itself.”

The telestereoscope was first described in 1857 by the German physician and physicist Hermann von Helmholtz, who is best remembered for his treatise on the conservation of energy, and for inventing the opthalmoscope. The device uses widely separated mirrors to artificially increase intra-ocular distance and exaggerate the user’s perception of depth, giving “a much clearer representation of the form of a landscape than the view of the landscape itself.”

In 2000, a group of artists reconstructed the telestereoscope for the Burning Man Festival. The machine is mentioned briefly in one of my favorite books, Instruments and the Imagination by Thomas Hankins and Robert Silverman.

by Thomas Hankins and Robert Silverman.

For those interested in building their own head-mounted telesterescopes, there is a java applet to help you calculate mirror angles and field of vision.

For the last three weeks, I’ve been in the Congolese rainforest, almost completely incommunicado thanks to a finicky satellite phone. While I was away, my first ever segment for NPR’s Radiolab aired, as part of an episode devoted to the subject of speed.

For the last three weeks, I’ve been in the Congolese rainforest, almost completely incommunicado thanks to a finicky satellite phone. While I was away, my first ever segment for NPR’s Radiolab aired, as part of an episode devoted to the subject of speed.